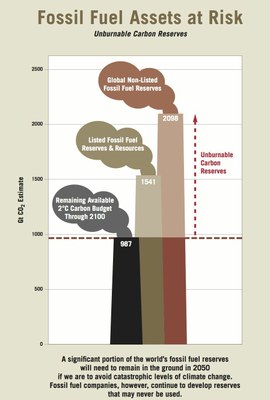

On several occasions over the years I’ve written about “stranded assets”. These can be categorized in more than one way. The article below discusses the cost that is on the books of companies of physical assets above ground such as plants and equipment that will become worthless as renewable energy pushes fossil fuel burning plants out of business. There is also the cost of writing off the value of fossil fuels still in the ground such as oil. You see, accounting rules allow oil companies to capitalize these assets before they are pumped. There are trillions, of dollars of these assets on corporate balance sheets.

https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2015/jan/08/new-study-urges-leaving-fossil-fuels-in-the-ground-whats-the-impact-for-business

Not only do they support these public companies’ stock prices but are collateral for loans from our biggest banks.

You may feel that simply making these assets worthless as the world turns away from fossil fuels is OK and that the corporations who will suffer is just a cost of doing business and a risk that they, and their shareholders, took so should be fully responsible for the consequences.

On the other hand, there may be very good reasons to construct ways to allow these businesses to find a way to transition out of the value of these stranded assets in a way that benefits everyone. After all, we don’t want to trigger another financial crisis and without getting into the reasons this might happen here, this would be very bad for us all and most likely hinder the transition to renewable energy. Ideally, the process could be designed to actually provide strong incentives for shutting down the burning of fossil fuels and speed shutdowns and transition.

The following article talks about a specific coal plant that is closing and pivots into the broader issue and discusses one idea such as securitization. Take a look at the article in full if this interests you.

While I am no expert on this topic, I do want to introduce this whole concept to you so that you can keep an eye on this especially as it may relate to your personal investments. If anyone reading this can provide greater insight into this dilemma please let me know.

“But while the plant sits idle, the meter is still running for consumers and likely will for the next 20 years until the remaining balance on the plant is repaid, as well as a profit for shareholders.

Milwaukee-based We Energies said customers will nonetheless save money — a lot of it — compared with what they would pay if the plant had continued to run. The utility estimates net savings of $2.5 billion, mostly in avoided operating and maintenance costs and capital investments.

United States has reached “the coal crossover,” at which renewables could replace almost 75% of the U.S. coal fleet and at an immediate savings to customers. By 2025, the number is set to rise to 86%.

They’re also leaving behind millions of dollars of so-called stranded costs on the companies’ books — costs someone must shoulder.”

‘Stranded Costs’ Mount as Coal Vanishes from the Grid

Jeffery Tomich

E&E News Reporter

Wednesday, May 29, 2019

But while the plant sits idle, the meter is still running for consumers and likely will for the next 20 years until the remaining balance on the plant is repaid, as well as a profit for shareholders. The tab will approach $1 billion over the next two decades, according to recent filings with the Wisconsin Public Service Commission.

Milwaukee-based We Energies said customers will nonetheless save money — a lot of it — compared with what they would pay if the plant had continued to run. The utility estimates net savings of $2.5 billion, mostly in avoided operating and maintenance costs and capital investments.

Pleasant Prairie’s situation isn’t unique. Across the country, utilities are shuttering older coal plants as they’re squeezed out by cheaper, cleaner alternatives. Many others are expected to join the list as renewable and battery storage costs continue to fall.

A study by consultants Vibrant Clean Energy LLC and Energy Innovation said the United States has reached “the coal crossover,” at which renewables could replace almost 75% of the U.S. coal fleet and at an immediate savings to customers. By 2025, the number is set to rise to 86%.

But in most cases, what’s left behind as utilities pull the plug on old coal plants is more than industrial shells awaiting demolition. They’re also leaving behind millions of dollars of so-called stranded costs on the companies’ books — costs someone must shoulder.

Consumer advocates are still crunching the numbers tied to the Wisconsin plant’s closure. Tom Content, executive director of the Citizens Utility Board of Wisconsin (CUB), a utility watchdog, said the group is still evaluating whether shutting the plant was in customers’ best interest.

The group doesn’t dispute that We Energies should get to recover its investment in Pleasant Prairie, which served customers for more than three decades before changing market forces made it uneconomical. But the group is questioning whether the utility should earn a 10% return on that investment, an amount that exceeds $350 million, if the plant is sitting idle.

“The question really comes back to, ‘Is it used and useful for the ratepayers in 2020?'” asked Content.

In deregulated states like Ohio, companies must write off the plants’ value (unless they get subsidies). That’s what American Electric Power Co. did in 2016 when it wrote off $2.3 billion to align the value of its Ohio generating fleet on its books with the actual market value.

But in more than two fully regulated states, such as Wisconsin, monopoly utilities say the “regulatory compact” entitles them to recover those stranded costs and earn a profit.

“From the utility perspective, there’s not a burning need to change that system because they’re guaranteed a return on equity,” said Jeff Waller, a principal with the Rocky Mountain Institute’s sustainable finance practice.

For others, the stranded cost issue is increasingly seen as a barrier to speeding up the shift away from coal. That’s because shutting down older generation and replacing it with new, cleaner plants could saddle customers with paying for both at the same time.

That’s a concern for consumer advocates in Wisconsin, a state that already has the second-highest retail electric rates in the Midwest.

Earlier this year, Gale Klappa, the CEO of WEC Energy Group, We Energies’ holding company, told analysts the company may file for approval of a utility-scale solar project. More recently, he suggested there could be additional coal plant shutdowns if the company determines, like in the case of Pleasant Prairie, there are cheaper options available.

For now, utility spokesman Brendan Conway said in an email that We Energies has no immediate need to replace energy and capacity from Pleasant Prairie. And even if capacity is needed in the future, the savings from closing Pleasant Prairie are so significant that customers would still save more than $1 billion.

‘Grand bargain’

Environmental and consumer advocates, utilities, and regulators across other states in the coal-heavy Midwest are trying to find balance between cutting carbon and keeping utility bills affordable.

A potential solution to accomplish those goals is securitization — refinancing higher-cost debt with low-interest, ratepayer-backed bonds.

The concept isn’t new. It was used in Florida to save money when utilities rebuilt the grid following hurricanes in 2004 and 2005. More recently, legislation in the same state enabled the issuance of $1.3 billion in bonds to cover the cost of the early retirement of Duke Energy Corp.’s Crystal River Unit 3 nuclear reactor, saving hundreds of millions of dollars.

The latest application for securitization is helping accelerate the shift to clean energy.

In recent weeks, New Mexico, Colorado and Montana legislatures have passed securitization bills. Lawmakers in Kansas and Missouri held hearings on similar measures. And parties in other states, including Wisconsin, have talked about it.

Ashok Gupta, a senior energy economist for the Natural Resources Defense Council, helped craft the bills debated in Missouri and Kansas, states where coal fueled 73% and 39% of electricity generated by the states in 2018, respectively.

While utilities opposed the bills, he believes changes can be made to win their support for legislation, which is necessary to get rock-bottom interest rates that are the linchpin of securitization programs.

Gupta is careful when talking to legislators in deep-red states — where climate change isn’t a policy drive — to emphasize that securitization is a financing tool, not a coal killer.

Done right, he said, its uses go beyond helping cut carbon. It can benefit consumers by holding down electric bills, and it can keep utilities whole financially, or better. Lowering interest payments on coal plant debt can enable utilities to make new capital investments in renewables, grid modernization or electric vehicle-charging infrastructure.

“That’s the grand bargain here,” Gupta said. “Securitization creates more headroom to do the things that can be done and should be done.”

Back in Wisconsin, the issue of stranded costs has already been teed up for debate by utility regulators, environmental and consumer groups, and utilities, including We Energies.

New PSC Chairwoman Rebecca Cameron Valq listed stranded costs associated with aging coal plants as an issue at the top of her mind.

And just weeks ago, officials with We Energies and utility Alliant Energy Corp., the Wisconsin PSC staff, the Sierra Club, and CUB gathered with other industry experts at Sundance Mountain Resort in Utah as part of the Rocky Mountain Institute’s e-Lab accelerator program to discuss securitization and the role it could play in Wisconsin’s transition away from coal.

Content, the consumer advocate, wasn’t part of the meeting. But a CUB financial analyst did attend.

Like Gupta, Content believes there’s potential for a grand bargain.

“I think there’s hope that all sides can coalesce on this issue,” he said. “If we’re in the middle of this energy transition, then let’s do it in the most orderly and cost-effective way possible.”