The last article I sent focused on dangerous heat events occurring all over the world but especially devastatingly in SE Asia. This article delves into developing knowledge and research into the complications of how the changing climate is not linear but rather causing multiple factors of climate change to interact making climate disaster events exponentially worse. Scientists are learning more and more about what to expect and how to predict what our future is going to look like in this developing field of study and knowledge.

One of the principal and important reasons that this knowledge is so critical is that we need to know what’s ahead of us so we can create building codes and define flood zones to be resilient and cognizant of possible events like flooding. Most codes are written based on past experiences. This is a formula for failure since our past is no longer a valid basis for predicting future events. We are in a whole new set of circumstances now.

For example, a building code may stipulate construction requirements based on a 100 year flood. But 100 year floods are happening every couple of years now and so building to the old standard is a recipe for calamity.

“From a scientific standpoint, research on compound climate events provides a unique insight into the complex, often interconnected workings of the global climate system — how different types of climate events influence one another and what their interactions might reveal about the Earth’s climate future.”

“research has begun to reveal that the influences of multiple factors in a compound event are “not linear,””

“Unusually hot conditions during periods of dryness, for instance, are an example of a compound climate event. Such conditions can increase the risk of prolonged droughts or the outbreak of wildfires. And research has suggested that they’re becoming more likely worldwide (Climatewire, Nov. 29, 2018).”

“accurate flood risk assessments are critical for creating flood maps and for designing resilient infrastructure.”

“It’s clear that when two distinct sources of flooding combine in the same location — for instance, storm surge from one direction and river flooding from the other — they produce a worse outcome.”

With all the CO2 currently in the atmosphere and the amount we’re continuing to pump into it no matter how quickly we can move beyond a fossil fuel economy, we are irrevocably progressing to a much hotter world. Society has to anticipate this new paradigm and plan for it as best we can. Waiting any longer to do this will only amplify our consequences later.

Ever Heard of ‘Compound’ Disasters? It’s New to Experts, Too

Chelsea Harvey

,Wednesday, July 3, 2019

One takeaway is the phenomenon known as “compound flooding,” the idea that disasters can be influenced by more than one source of water at the same time.

Several studies have concluded that global warming likely boosted the hurricane’s record levels of rainfall. Scientists have also pointed to the storm’s unusual stalling behavior as a potential glimpse of the climate future, with some research suggesting that climate change may drive an increase in persistent, long-lasting weather systems.

But it was the storm’s catastrophic flooding, driven by a combination of storm surge and river flooding forced by unprecedented rainfall, that may provide its most important lesson.

Perhaps more than any other recent disaster, Harvey drew attention to compound flooding. As scientists are increasingly discovering, the combination of two or more sources of flooding can be much worse than the projected impact of an individual one.

And as sea levels rise and storms produce more rainfall, scientists say their combined influence is becoming more formidable.

“Sea-level rise, it will increase your baseline, your tide and surge,” said Amir AghaKouchak, an engineer and hydrology expert at the University of California, Irvine. “So you have this changing risk, at least from one component, which is the ocean water level — but possibly also rainfall extremes.”

Floods aren’t the only category of compound climate events. There are a wide variety of climate and weather phenomena that are becoming more likely to occur at the same time.

Unusually hot conditions during periods of dryness, for instance, are an example of a compound climate event. Such conditions can increase the risk of prolonged droughts or the outbreak of wildfires. And research has suggested that they’re becoming more likely worldwide (Climatewire, Nov. 29, 2018).

It’s a field of study that’s quickly gaining traction. In May, Columbia University hosted a three-day conference devoted to the science of “correlated extremes,” showcasing research on a wide variety of compound climate events and other types of connected or co-occurring climate phenomena. The conference included presentations by researchers from around the world.

From a scientific standpoint, research on compound climate events provides a unique insight into the complex, often interconnected workings of the global climate system — how different types of climate events influence one another and what their interactions might reveal about the Earth’s climate future.

From a policy standpoint, research on compound flooding might provide some of the most immediate opportunities for climate adaptation.

“We knew forever that droughts and heat waves are related — but we don’t really bring this kind of knowledge into risk assessment and mainly practical applications,” AghaKouchak said. On the other hand, accurate flood risk assessments are critical for creating flood maps and for designing resilient infrastructure.

“Flooding is more important than others because it’s closely related to our design guidelines,” he said.

A developing science

AghaKouchak is one of a relatively small group of researchers specializing in the improvement of compound flood risk assessments. The goal is to develop methodologies that can be eventually applied to policy, including the mapping of flood zones and the design of flood protections.

It’s tricky science.

It’s clear that when two distinct sources of flooding combine in the same location — for instance, storm surge from one direction and river flooding from the other — they produce a worse outcome. Scientists already have well-developed methods for modeling and assessing flood risks from single sources. So it seems logical that they could predict the outcome of a compound flood by simply adding up the results of individual risk assessments for each source the compound flood involves.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency guidelines for flood maps and risk analyses incorporate this kind of technique for situations involving floodplains subject to the influence of multiple sources of flooding.

But research has begun to reveal that the influences of multiple factors in a compound event are “not linear,” according to Thomas Wahl, a civil engineering professor at the University of Central Florida. In other words, you can’t just add them together and assume it’s correct. Recent studies have demonstrated that it might underestimate flood risks.

Researcher Antonia Sebastian of Texas A&M University has published multiple papers investigating the incidence of flood claims occurring outside FEMA’s flood maps. One of the most widely cited analyses, focused on the Houston suburbs, found that the agency’s 100-year floodplain maps missed about 75% of the damages claimed during five severe floods between 1999 and 2009.

Underestimates of compound flood risks are likely just one reason this may have occurred, Sebastian noted. But, she added, “that was kind of like the underlying observation that drove a lot of my research into compound flooding.”

At the Columbia conference in May, AghaKouchak presented findings from a recent study he co-authored, led by Hamed Moftakhari of the University of Alabama, outlining one new statistical method for compound flood risk assessments.

As the paper points out, strategies like the FEMA guidelines employ a method known as a univariate analysis, which analyzes one variable at a time. AghaKouchak and colleagues instead suggest a type of multivariate model, which allows for the analysis of several connected drivers at once. Between the two, the research suggests that the univariate approach is more likely to underestimate risks when applied to compound flooding situations.

But while the Moftakhari paper outlines one potential new method, the field as a whole is still largely in the development stage. There are other groups working on similar methods, with no single “correct” strategy yet established.

For now, when it comes to policy, “it’s hard to directly integrate this [work] as there’s no clear guidelines and no clear agreement across the scientific community which exact efforts out of these hundreds of different tools we have, which is the best to use in this situation,” Wahl said.

Gradual advancements in both statistical methods and hydrological and climate models have enabled the research to gather traction over the last few years. But there are a variety of challenges researchers still face.

According to Wahl, assessing compound flood risks requires the merging of different procedures. It needs both a hydrodynamic model that can represent all the different factors playing into a compound flooding event and a statistical method to analyze the risks. Scientists are still improving both of these components.

The challenge becomes more difficult with more factors and more complex landscapes, says Moftakhari, the University of Alabama researcher.

“If we say there are hundreds of possibilities for the downstream conditions, which is ocean levels, and hundreds of possibilities for the upstream conditions, which is river runoff or rainfall, the combination of these would be tens of thousands,” he told E&E News. “So we are not able at the moment to run our numerical models for all those combinations.”

The situation gets even more complicated when considering the growing influence of climate change, Wahl added.

“Then we have to talk about whether the climate models are capable of resolving the processes that lead to compound events, whether the resolution is high enough, whether all these independent processes are represented well enough by climate models,” he said.

All of the different components are steadily making progress, Moftakhari noted. It’s putting them all together that takes the most work.

“The statistics is growing so fast, numerical modeling capacity is growing so fast — but how we can integrate them and merge them in a meaningful way to be able to represent the actual events in reality in a meaningful way?” Moftakhari said. “That’s to me the big challenge, which opens up a direction to improve on the FEMA maps.”

Waiting for ‘actionable science’

After the devastation wrought by Hurricane Harvey, coastal Texas has become a priority zone for improved flood protections.

The Army Corps of Engineers Galveston District is working on its largest-ever civil works project, which aims to update existing flood protection systems in Jefferson and Brazoria counties, not far from Houston, and to construct a new coastal storm risk management (CSRM) system in nearby Orange County. Currently in its preconstruction phase, the new system will likely be composed of about 27 miles of levees and flood walls, according to Eddie Irigoyen, an Army Corps project manager for the Galveston District.

In the process, the agency has identified an opportunity to investigate the potential impacts of compound flooding events.

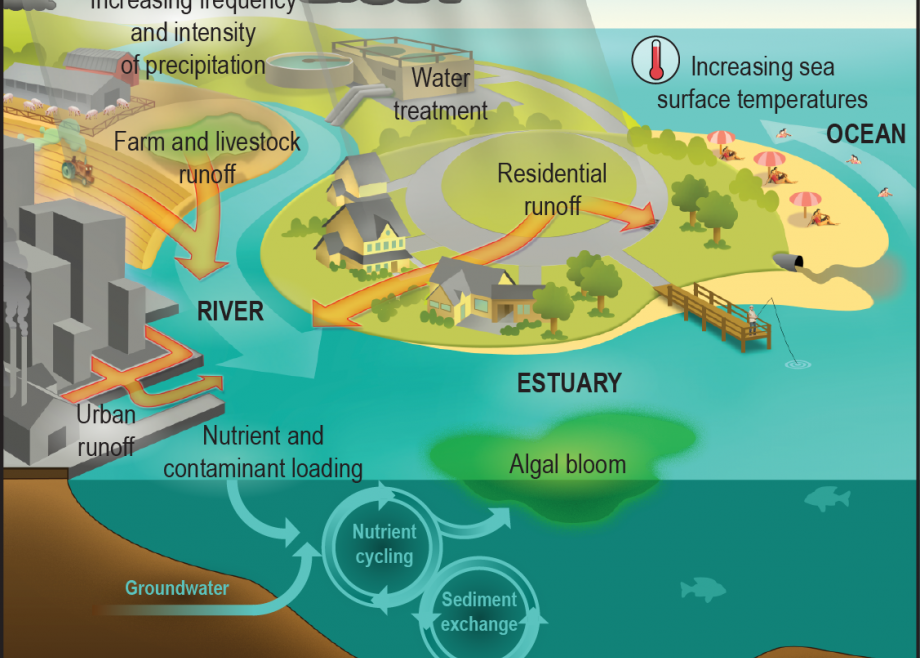

Orange County sits just north of Sabine Lake, a 90,000-acre estuary at the border of Texas and Louisiana. The lake itself rests snugly between the Gulf of Mexico to the south and a converging network of rivers to the north. It’s exactly the type of landscape likely to be prone to compound flooding during severe storms, with the combined risk of both storm surge and overflowing rivers.

The primary focus of the Army Corps project revolves around the mitigation of coastal hazards, like storm surge and wave action, according to Shubhra Misra, a hydraulic engineer in the Galveston District’s Hurricane Flood Risk Reduction Design Branch. In an email, he added that “rainfall-induced interior flooding and interactions of rainfall-induced flows with coastal surge are important drivers toward informing a holistic risk-based design and accounting for the various sources of flooding risk to the CSRM system.”

With that in mind, the Army Corps is working closely with various researchers, including scientists at the University of Texas and Wahl’s research group at the University of Central Florida, to explore strategies in the kinds of numerical and statistical modeling that may be used in compound flood risk assessment.

The Galveston District hosted a workshop in April focused on compound flooding driven by storm surge and rainfall-induced river flow. The workshop invited experts from the Army Corps, USGS, NOAA, FEMA and other scientists from across the nation.

Coastal Texas has already proved itself a prime testing ground for research on compound floods and potential applications for policy, according to Sebastian, the Texas A&M researcher. While Harvey was the costliest storm to strike the Gulf Coast since Hurricane Katrina, it wasn’t the first to begin raising concerns among researchers.

“These conversations all started after Hurricane Ike in 2008,” Sebastian said in an interview. “Harvey was the culmination of everything everybody had worried about for a while.”

In the wake of the damage inflicted by Ike, agencies like the Army Corps began exploring options for increased coastal protections, and researchers in the area began evaluating the pros and cons of different proposals and investigating new ways to evaluate the conditions that might influence flood hazards along the coast.

“The research group I was a part of as a Ph.D. was focused on quantifying the benefits of these different strategies,” Sebastian said. “And in looking at the strategies, it became really obvious that there was a need to consider both rainfall runoff and storm surge.”

Today, the ongoing projects in the Galveston District may speak to a growing interest from federal agencies in what’s now a rapidly developing field.

“I think all of FEMA, also NOAA, Army Corps — they’re all aware of the work, and I think they are interested in incorporating these things,” Wahl said.

But while researchers are gradually identifying opportunities for improvement, there’s still a long way to go before the science can be converted into policy, said Army Corps engineer Kathleen White, who leads the agency’s Climate Preparedness and Resilience Community of Practice and who encouraged the Galveston District’s April workshop on compound floods.

“We don’t make infrastructure decisions based on the latest science, we make those decisions based on the best available and actionable science,” she said in an interview. “So best available and actionable is different than latest.”

For now, she said, the concept of compound climate events has been identified by the Army Corps as a gap area with potentially important implications, and the agency is closely tracking advancements in the science of risk assessments. But there’s a need for more confidence in the developing methodologies, and a consensus among scientists about the best approach, before it can be applied to new policies, White said.

“Here we are in an emerging area — it’s exactly what you want,” she said. “You want a lot of diversity of perspectives and approaches, so that if they begin to coalesce into something with a lot of common elements, then you feel more confident in using them.”