Here in the Midwest Great Lakes states, our congressional delegations have successfully fought for and created the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI), a $300-million-per-year program that began in 2010 and was made official last year by Congress. It is making a HUGE difference in restoring the health of the Great Lakes and the communities along their shores. One local site is Waukegan, a superfund site that is gradually being remediated. (Now we just need to shut down the lakeside coal fired power plant there so the local community can enjoy the basic environmental benefits of clean air and water we ALL have a right to expect.) As the article below states:

“We view the Great Lakes as part of our DNA,” Stabenow said, noting the importance of tourism, a $16 billion boating industry, a $7 billion fishing industry and the drinking water supply for 40 million people. She said she’ll fight “at every turn” of the budget process in order to keep the money flowing.

And yet, the proposed Trump budget calls for a 97% reduction of the fund from $300,000,000 to $10,000,000. At that level, why even bother? Why not just completely eliminate it altogether??? Who needs clean, safe drinking water anyway? Let’s just trash the Great Lakes for the sake of… just what I’m not even sure. Does this make any sense to you? Let’s let the states or local governments pay for the cleanup that industries created? Like those states and municipalities have the funds.

“GLRI, at $300 million per year, is a few percentage points of EPA’s annual budget. EPA spending is a small sliver of the overall federal budget.”

The insanity of this to me is beyond comprehension. But, what about Trump makes any sense???

As I keep saying…. this is really, really bad, bad, bad. RESIST!!!

Great Lakes communities gear up to battle Trump’s budget

Emily Holden, E&E News reporter

Published: Friday, March 17, 2017

Sheboygan River The Sheboygan River was once one of the dirtiest in the country, containing industrial pollutants that can cause dire health effects. After more than $100 million in spending, including $58 million from a U.S. EPA program the Trump administration wants to eliminate, the river is in much better shape.

SHEBOYGAN, Wis. — On a below-freezing day on the shore of Lake Michigan last week, families splashed around in a steamy 84-degree waterpark inside the massive Blue Harbor Resort.

The hotel at the mouth of the Sheboygan River in 2004 replaced a dirty brownfield site that had been used for more than 100 years to build ships and store lumber, coal, petroleum, salt and fertilizer.

Since then, local, state and federal officials have rehabilitated the waterfront and removed toxic pollutants from the river that winds through the large town around coffee shops, parks and new shanty-style restaurants built to look like fishing shacks.

Together officials say they’ve spent more than $100 million on the effort, including about $58 million from U.S. EPA programs in the Great Lakes that the White House now wants to eliminate.

Industrial facilities upriver had for decades polluted the Sheboygan River and the sediment below with substances that are now known to cause cancer in animals and are likely to do so in humans. Manufacturers and other industries flocked to the Upper Midwest for natural resources and easy water access. But over time, they closed up shop to seek cheaper workforces, to rely more on machines or simply because demand for their products declined.

In their wake, they left a regionwide environmental mess.

“You can only sustain that kind of boost for so long until you see the kind of erosion that we have seen,” said Cameron Davis, who coordinated federal agency action on the Great Lakes under the Obama administration’s EPA. “The jobs bled out. The ecosystem began to bleed out. And the quality of life in the region began to bleed out.”

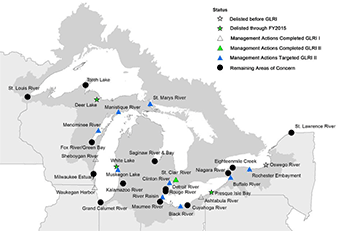

Great Lakes Areas of Concern

[+] Communities all around the Great Lakes are listed as “Areas of Concern,” meaning they are so contaminated with legacy pollutants that they can’t support animal habitat or fish safe enough to eat. Four have completed their work and been delisted. Four more are nearly done with cleanup projects but require further water testing and other steps. Nearly two dozen others have much more left to do. Map courtesy of the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative.

Enter the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI), a $300-million-per-year program that began in 2010 and was made official last year by Congress. GLRI offers funding to communities that have “taken a beating,” as Davis said. The program helps to clean waterways to make them more navigable and to draw people back to the shores. As climate change causes water level fluctuations and other problems for the lakes, that work will be more critical, Davis said.

Around the Great Lakes, eight sites have completed their work, but only four have finished testing and been delisted as problem areas. Four more are supposed to be done with cleanup this year. That leaves almost two dozen that still have major problems. Some are not done with multiple phases of dredging and restoration that would require more grants. Others have been planning to apply for funds but may never see them and may not be able to come up with the money otherwise. Responsible companies sometimes pay for parts of projects upfront but often contribute to further environmental efforts as part of settlement agreements after cleanup is complete.

The initiative also combats invasive species like Asian carp, restores native animal habitats and handles agricultural runoff that causes the kind of algae bloom that shut down the Toledo, Ohio, water system for a full weekend a few years ago.

Now this program is in the eye of President Trump’s budget storm. The administration’s decision yesterday to slash funding for the Great Lakes as part of a 31 percent spending reduction at EPA has galvanized Republicans as well as Democrats. A group of nine lawmakers led by Sens. Rob Portman (R-Ohio) and Debbie Stabenow (D-Mich.) sent a letter to the White House expressing their concerns, and yesterday, Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker (R) joined them in opposing the cuts.

That such a battle is shaping up in Wisconsin, which Trump won by about 22,000 votes in November, speaks to a brewing national tension. Conservatives may be itching to cut red tape, roll back regulation and shift money to defense — but supporters of programs like GLRI are loath to lose local dollars that they argue spur economic development.

Such clashes between the White House’s bottom line and thousands of lawmakers’ regional projects are expected to play out around the country in the coming months as policymakers grapple with Trump’s budget.

“We view the Great Lakes as part of our DNA,” Stabenow said, noting the importance of tourism, a $16 billion boating industry, a $7 billion fishing industry and the drinking water supply for 40 million people. She said she’ll fight “at every turn” of the budget process in order to keep the money flowing.

Healing the ‘black eye’ of Sheboygan

Sheboygan first realized it had serious water quality problems in the early 1980s when a local trapper named Roy Sebald noticed minks were no longer reproducing in the area and alerted authorities. Officials began testing the water and sediment and discovered polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, as well as heavy metals.

The main companies responsible were Tecumseh Products Co., which made engines using die casting, a process to force molten metal under high pressure into a mold, and Wisconsin Public Service Co., which operated a coal gasification plant.

In the late 1980s, the federal government named the lower portion of the Sheboygan River a Superfund site, a place contaminated enough with hazardous waste to be dangerous to humans. EPA also listed it as one of dozens of Great Lakes “Areas of Concern,” which are too degraded to support aquatic life that benefits humans.

“My dad grew up here in Sheboygan Falls, and he can remember swimming in the river here, and he’d get out and he’d feel like parts of him were glowing when he was done,” said Sheboygan County Administrator Adam Payne. “You had this beautiful river going through the heart of the community in Falls, Kohler, Sheboygan and out to Lake Michigan, and it was literally the black eye of the community.”

Over the years, local and state governments and companies responsible for polluting the Sheboygan River and surrounding areas have put up money for cleanup and restoration. The federal government provided an even bigger match. One recent project at the mouth of the river on the shore of Lake Michigan helped to keep sand on a beach near the city’s tourist zone in place. Photo by Emily Holden.

Signs lined the river: Don’t eat the fish. Don’t eat the ducks. Don’t swim, especially if you’re pregnant.

“Talk about a way to market the community,” Payne said.

So in 2009, the county put together a work group with the city, state, multiple federal agencies and the two businesses to cobble together a plan.

Local government contributed $600,000 and was allowed to count tens of millions of dollars that the companies that caused the pollution had previously spent on cleanup and dredging to qualify for a federal match.

Over the next several years, the area undertook several massive operations to dredge to remove concentrated areas of contaminated sediment, dry it out along the river’s shore and ship it to a licensed landfill. Officials then began projects to restore natural habitats.

Before then, the waters had been nearly unnavigable, according to fishermen. That’s because local officials were not allowed to deepen the river and the harbor area without cleaning up the pollution.

Several areas in the river were previously too shallow to travel, according to George Gahagan, who has been a fisherman in Sheboygan all his life and has worked for a charter sportfishing operation called Dumper Dan for 25 years.

A boat repair shop was inaccessible and had to meet people where they were. The mouth of the river was too high, elevated above the rest of the waterway, so salmon had trouble making their way in to spawn.

Gahagan called the difference the cleanup projects made to the community “night and day.” The harbor used to be a scary place after dark and now booms with locals and tourists on warm days, he said.

Business is better now, Gahagan said, even though officials are still testing the water and have not lifted warnings about eating the fish. If they eat it in moderation, he said, “people should have no fear at all.”

Information from the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources notes that PCBs collect in the bellies of fish. If humans eat those fish, PCBs can stay in their body fat for years. The pollutants can cause developmental impairments in children, harm the reproductive system, be associated with a higher risk of cancer, hurt the immune system and alter thyroid hormones.

Gahagan worries that with budget cuts, testing will stop and advisories will stay in place. He is also concerned that the Trump administration and Congress could nix funding that keeps invasive species from ruining his business.

He voted for Gary Johnson for president because he said he couldn’t bring himself to pick Trump or Hillary Clinton. He said he understands not everyone wants to fund waterway cleanup and protection. People have other interests.

“A lot of people in the world or in this country don’t really care about what happens in our area in the Great Lakes in the environment,” Gahagan said. “Most people wouldn’t even blink an eye by cutting stuff like that, but it definitely affects us.”

For Duluth, cuts are ‘devastating’

Where Sheboygan has completed most of its GLRI work, other communities are just getting started.

In Duluth, Minn., local groups and the state are still working to piece together funding to get a two-thirds match from GLRI to clean up damage from paper plants to the 15 miles of the St. Louis River that snakes through the major port city. Getting delisted would cost about $73 million, according to Mayor Emily Larson.

Duluth is simultaneously spending $18 million, leveraged to total $50 million, to make the river corridor a better place to live. The city has worked with EPA to turn old industrial sites that once leaked contaminants into the river into apartments, businesses and cleaner industry facilities.

Larson said big EPA cuts would be “absolutely devastating,” and she has no idea what Duluth will do if GLRI funds aren’t available.

“It is such a nonpartisan issue, it’s frustrating to see it get thrown into some kind of partisan boxing match,” Larson said.

Matt Doss, a Great Lakes Commission policy director who helps coordinate discussions among eight states and two Canadian provinces, said people who aren’t on the ground don’t understand why GLRI is so important.

“A lot of these communities that have lost industries that are on the shoreline — it’s not that we don’t want these industries to come back. But they’re probably not,” Doss said. That’s part of why cleanup is so important, to draw in visitors and other types of business, he said.

EPA dollars key to diversification

Sheboygan is a sleepy Midwestern city in the winter, with about 50,000 people living in the area and 115,000 in the broader county.

But it’s “still an economic powerhouse when it comes to manufacturing,” Payne said. About a third of people work in manufacturing. The unemployment rate is low, at about 3.6 percent on average last year, compared with 4.9 percent nationally.

Blue Harbor Resort employee Jhorell Benig

The Blue Harbor Resort on the shores of Lake Michigan in Sheboygan, Wis., was built over what was once a U.S. EPA-designated brownfield. The site stored lumber, coal and petroleum. Resort employee Jhorell Benig holds up a historical photograph of the land. Photo by Emily Holden.

Officials say that’s because dedicated family-owned companies have refused to move their operations. As industry changes, however, Sheboygan wants to diversify its economy and clean up the environment so people will want to visit and live by the river and Lake Michigan.

Already, apartments with nearly 350 units are popping up near the resort, next to the river and within view of the lake. Restaurants line the riverwalk. A new one that will serve barbecue and pizza is opening soon and has a “now hiring” sign posted.

Even though it was freezing, people last week made the voyage from Milwaukee and Chicago to spend spring break at the water park in Sheboygan. Couples bundled up in coats to walk on the beach, where the city had just used some GLRI funding on a project to keep the sand from constantly blowing away. One brave soul could be spotted surfing on Lake Michigan even though the high for the day was 28 degrees.

With the river mouth deeper after dredging, the city has signed up to be on the route for Great Lakes cruise ships. Travelers would stop for the day to shop and eat, boosting local sales. Sheboygan hopes they might come back later to visit the resort, surf or take sailing lessons near the yacht club.

The area also is applying to be designated as a national marine sanctuary, a place where divers could come to see underwater shipwrecks. It’s unclear whether that program, which is run by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, will move forward in the face of budget cuts.

Mayor hopes Trump will make a deal

Mayor Mike Vandersteen is proud of the cleanup work he’s helped coordinate as mayor and, before that, as chairman of the County Board. For visitors, he has a 2-inch binder from a previous presentation that is full of photos and explanations of the various projects over the years.

Mayor Mike Vandersteen

Mayor Mike Vandersteen, who was previously chairman of the Sheboygan County Board, has worked for years with a group of local, state and federal officials aiming at getting Sheboygan removed from a list of Great Lakes “Areas of Concern.” Photo by Emily Holden.

He says things are looking up in Sheboygan, even though the area has steps left to show that the water is clean and healthy. Visitor spending in Sheboygan County has increased every year since 2010. Vandersteen acknowledges it’s difficult to tell how much economic growth is because of the cleanup versus other factors. Anecdotally, he feels it has been a huge boon.

The mayor is a Republican, although he says that doesn’t come up much in his day-to-day activities. While he’s a big supporter of EPA’s water work, he has had fights with the agency about other issues, including air quality monitoring. He says Sheboygan is getting blamed for air pollution blowing in from industrial facilities in places like Gary, Ind.

Vandersteen recently spoke with the congressman who represents Sheboygan, Rep. Glenn Grothman (R), who later told E&E News he supports cutting EPA’s spending but does not want to eliminate GLRI, which he called a “very worthy program.”

“It’s going to be a tight budget on everything but military and transportation, given the $20 trillion debt,” Grothman said Wednesday. “There may be a small cut there, along with small cuts to everything else, but I will fight to prevent it from being more than a minimal reduction.”

GLRI, at $300 million per year, is a few percentage points of EPA’s annual budget. EPA spending is a small sliver of the overall federal budget.

Vandersteen said he read Trump’s book “The Art of the Deal.” He knows Trump likes to start with an extreme position so that he’s still happy after compromising.

“I’m hoping this is one of those situations where it’s not going to be as bad as what it looks,” he said.

Twitter: @emilyhholden Email: eholden@eenews.net