I started going to the mountains as a little kid back in the 50’s when my family would spend summer vacations at Sun Valley, Idaho. I started camping and canoeing when I was 9 and backpacking when I was 19. I’ve never stopped.

1971 – My First Backpacking Trip: Shenandoah National Park along the Appalachian Trail

Recently in Idaho

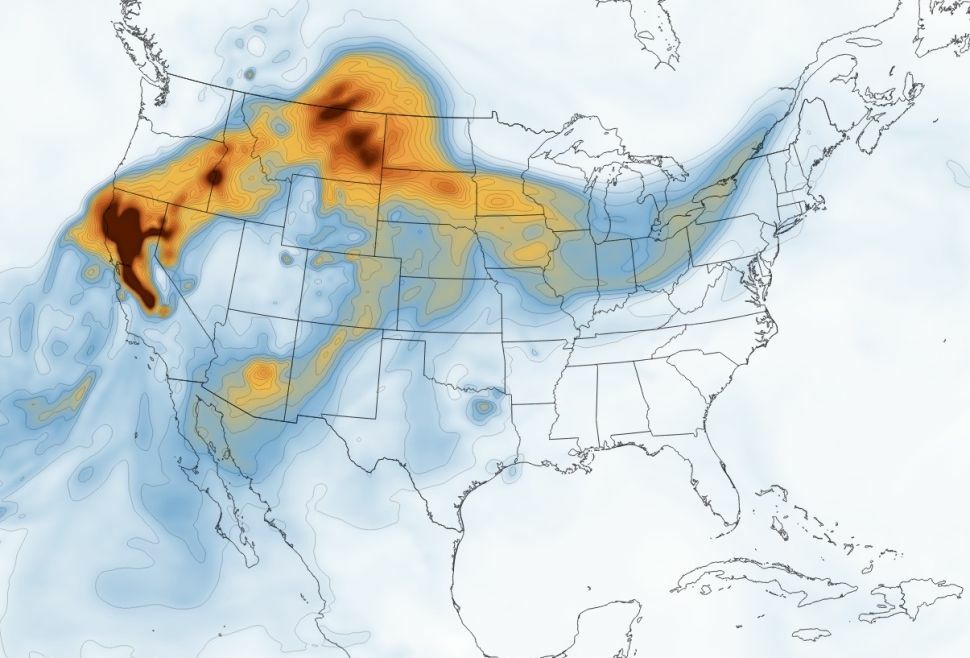

It used to be that I would go to the wilderness to get away from urban air pollution–to smell the pines, breath the clean mountain air and enjoy the magnificent vistas. Decades later, great progress in cleaning up our skies has made the air we breath here in Chicago dramatically better but climate change has made western skies unbreathable on many days.

1977 The Chinese Wall in the Bob Marshall Wilderness, Northern Montana

Recently in the Sawtooth Mountains, Sawtooth Wilderness, Idaho

Those of you who have been reading my missives for over 2 decades know that I have been wailing about climate change being real and that the affects will be bad and effect all our lives in predictable and UNPREDICTABLE ways. It’s sad to see this coming true and that only now is there beginning to be a sense of urgency. Better late than never. (Do you hear that Republican Party???)

Fires out west have made air quality so bad it’s not healthy to spend time outdoors in the mountains. And at the same time, the predictable increasing frequency and intensity of hurricanes is wreaking havoc on locales in their paths. It’s a shame that it has had to come to this to motivate action. Mitigation is going to cost a lot more but what alternative do we have?

“Scientists have known for years that climate change is making hurricanes more powerful and destructive. Warmer waters along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts provide more energy to storms, and rising seas create storm surges that can be orders of magnitude higher than in past hurricanes.

More recently, scientists have observed storms rapidly intensifying over relatively short periods of time and distances. That was the case with Hurricane Michael in 2018 and now Laura.

“Specifically, near Louisiana, I haven’t seen this kind of rapid intensification from Category 1 to 4 just close to landfall,” said Hiroyuki Murakami, a tropical cyclone expert at NOAA.

While no two hurricanes share matching characteristics, even across centuries, it has taken only 15 years to break records, or nearly so, that have lasted 180 years with regard to the three defining metrics of hurricanes: surge, rainfall and wind speed.”

Hurricane Laura Shattered Lives, Property … and Records

Daniel Cusick and Chelsea Harvey E&E Reporters

Friday, August 28, 2020

Hurricane Laura plunged into the southern U.S. yesterday as it moves toward the Mid-Atlantic after making landfall. cdn.star.nesdis.noaa.gov

Hurricane Laura will exceed both Katrina and Harvey in one critical metric — sustained wind speed.

Peaking at 150 mph at landfall in Cameron, La., Laura’s top onshore wind speed was 25 mph greater than Katrina’s and 20 mph greater than Harvey’s, based on historical data from NOAA.

Only one other Louisiana storm matches it, the 1856 “Last Island” hurricane, which also packed maximum winds of 150 mph. Just four other U.S. storms have recorded higher winds at landfall than Laura.

“Regardless, we’re splitting hairs here. It’s going to rank at or very near the strongest storms to ever hit Louisiana,” said Barry Keim, the Louisiana state climatologist and co-author of “Hurricanes of the Gulf of Mexico,” a history of Gulf storms from the 19th century through Hurricane Ike in 2008.

Does it matter where Laura lands in the mix?

Maybe.

Scientists have known for years that climate change is making hurricanes more powerful and destructive. Warmer waters along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts provide more energy to storms, and rising seas create storm surges that can be orders of magnitude higher than in past hurricanes.

More recently, scientists have observed storms rapidly intensifying over relatively short periods of time and distances. That was the case with Hurricane Michael in 2018 and now Laura.

“Specifically, near Louisiana, I haven’t seen this kind of rapid intensification from Category 1 to 4 just close to landfall,” said Hiroyuki Murakami, a tropical cyclone expert at NOAA.

While no two hurricanes share matching characteristics, even across centuries, it has taken only 15 years to break records, or nearly so, that have lasted 180 years with regard to the three defining metrics of hurricanes: surge, rainfall and wind speed.

All occurred in the Gulf of Mexico.

Katrina’s storm surge was between 24 and 28 feet along coastal Mississippi. That’s the highest ever recorded in the Western Hemisphere, according to NOAA. The storm overtopped New Orleans’ outdated levees and flood walls, eventually killing more than 1,700 people.

Harvey, 12 years later, dumped 60.6 inches of rain at Nederland, Texas, the most for any landfalling tropical system. It killed 105 people and destroyed 300,000 structures.

And yesterday, Laura completed the trifecta with its maximum wind of 150 mph at Cameron, the highest recorded in Louisiana and tied for second- or third-highest in the Gulf behind Michael in 2018.

Hurricane Camille landed on the Mississippi border with Louisiana in 1969 with maximum sustained winds estimated at 200 mph, but no official records exist because the storm destroyed all wind-measuring instruments, according to NOAA.

Laura also met the speed test, swelling from a tropical storm early Tuesday morning to a monster Category 4 by Wednesday afternoon. It rammed into Louisiana hours later.

The National Hurricane Center defines a “rapid intensification” event as a hurricane that increases its wind speeds by at least 35 mph in a 24-hour period. Experts say several factors contribute to that process.

In addition to warm water, hurricanes favor lower wind shear and minimal changes in wind speed or direction at different heights in the atmosphere. Laura benefited from both, accelerating its wind speed by a whopping 65 mph over 24 hours.

Similarly, Hurricane Michael — which destroyed Mexico Beach, Fla., in October 2018 — developed from a Category 2 to a Category 5 storm in 24 hours as it approached the Panhandle. Hurricane Harvey also grew from a Category 1 to a Category 4 storm over 24 hours before slamming into the Texas coast in 2017.

All of them occurred within a four-year period.

That’s a big concern for coastal communities. Rapid intensification events aren’t easy to predict, giving less time for people to prepare.

Laura’s storm surge was also a significant factor in the storm’s destructive power, as stronger winds tend to pile up water as they move toward the shore.

As Laura approached the coast Wednesday, the National Hurricane Center warned of a 15- to 20-foot “unsurvivable” storm surge that could penetrate up to 40 miles inland.

Reports from Lake Charles, La., indicated that the surge there was closer to 5 feet. Information for points east of Cameron, including low-lying areas expected to see the highest surges, was still being collected yesterday afternoon.