When you think of climate change what do you think of? Do you think about how it will affect you personally? Or how it may affect others? Do you worry about hurricanes? Tornados? Flooding? Sea level rise? Storm surge? Fires? Drought? Mud slides? Heat waves? Travel delays? Economic impact? Refugees? War? All of our lives are most likely are going to be, or currently are, feeling the effects of a warming climate. We here in Chicago just lived through a very hot weekend that experienced heat and air quality warnings. My wife, who has asthma, despite staying indoors most of the time, still suffered with breathing. We are fortunate though. We are able to stay in our air conditioned home and get by reasonably well.

There are those that don’t have the good fortune with which so many of us are blessed. Every day they face the consequences of heightened heat on their health and economic opportunity. The following article brought this front and center to me. It brings home the very real and current impact our behavior is having on peoples’ lives every day.

It is easy to pontificate about climate change while I live in a nice home, drive my cars (granted that ours are both fully electric), travel by airplane and otherwise contribute more than my fair share to greenhouse gases. None of us is pure and without responsibility. Unless you live in a cave you’re adding to the problem. (Even if you lived in a cave you’d probably be cooking with a wood fire and producing CO2.) The question for me is what you can and are doing to try and transition our society from burning fossil fuels that are destroying the climate and threatening our civilization. As we used to say in our youth so many decades ago, “if you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem.”

Meanwhile, the impact described in the following article is tragic, heartbreaking and scary. And it brings to the forefront how inequitable the consequences are in that people on the low end of the economic scale are disproportionately impacted.

“As climate change intensifies heat waves and drought and helps spread diseases carried by mosquitoes, the life of a farmworker in this fertile part of Texas is getting harder and more dangerous.”

“The heat is cutting into work hours by driving people out of the fields. It’s also destroying some crops before they can be harvested”

“Farmworkers labor in the sun during dangerous heat waves because they can’t afford to take days off, said Jose Torres, a former farmworker who is now a paralegal at Texas RioGrande Legal Aid. Complaining about conditions, such as dirty or warm water, a lack of bathrooms or a 105 F day, could result in being blacklisted. Farm bosses want people who work, not who complain, Torres said.”

“Recurrent dehydration can have serious health consequences, and medical researchers said the incidents are on the rise in South Texas.

As global temperatures climb, so, too, does the incidence of fatal kidney disease. It’s on the rise among farmworkers throughout the world. A 2014 study of farmworkers in Central America, many of them young males, found that a high number died from an unknown kidney disease. Researchers connected the deaths to recurrent dehydration and a heavy workload in hot conditions. It has killed about 20,000 people in Central America in the last 20 years, according to researchers at Boston University.”

“When heat causes blight that ruins a 50-acre field of onions, the farmer can be compensated, said Linda Martinez, who runs a crew of farmworkers. The workers don’t have that choice, she said, and it’s driving more young people away from the fields and into restaurants, Walmart and other places where the work is not so grueling.

That makes it harder to find workers, Martinez said. In the past, she could have a crew of 300. Now, it’s hard to get 150 because younger people are turning to other work.”

This Texas County is Very Worried About Warming. Here’s Why

Migrant field hands picking watermelon at a Texas farm. Climate change is making farmworkers’ already grueling jobs even harder. Jacob Ford/Odessa American/Associated Press

As climate change intensifies heat waves and drought and helps spread diseases carried by mosquitoes, the life of a farmworker in this fertile part of Texas is getting harder and more dangerous.

For Puente, it also means less money. And she doesn’t have much to begin with.

The heat is cutting into work hours by driving people out of the fields. It’s also destroying some crops before they can be harvested, Puente said after a recent shift. It was noon in late March, and temperatures had surpassed 90 degrees Fahrenheit.

“When we work less hours, it’s less income,” Puente said through a translator. “Sometimes we won’t even work the eight hours.”

The residents of this borderland have an unusually high level of concern about climate change. Hidalgo County is home to the largest percentage of people in Texas who accept that climate change is happening and who worry about it. It also stands out nationally for its views on rising temperatures.

Seventy-one percent of county residents are concerned about climate change. That’s 4 points higher than in Travis County, home to liberal Austin. The polling was conducted by Yale University’s Program on Climate Change Communication.

That’s a lot higher than the national average. A little more than half the U.S. population says it’s worried, according to Yale. Researchers have also found that Latinos worry about climate change at a higher rate than whites. In South Texas, concern about the climate is largely driven by the preponderance of farmworkers, who live in sprawling neighborhoods called colonias in the border counties of the Rio Grande Valley.

Those numbers only tell part of the story.

In New York City and Washington, D.C., where most people say they worry about global warming, the issue is often filtered through an intellectual lens.

In Hidalgo County, they experience a warming world while they’re in the fields. Sometimes, they see onions yellow and wither before they’re harvested, taking a day’s pay. Some worry that their babies could be born with small heads if mosquitoes from the irrigation canals slip through a hole in the screen. Others watch a hand-dug well in their backyard begin offering brown water before going dry.

Farmworkers are one of the country’s most vulnerable populations to climate change. Soaring temperatures and drought strain their bodies at work, but their living conditions also create stress.

Many colonias, which feature a mix of ramshackle shacks and modest brick homes, are built in floodplains. Others are carved into former farm fields and lack drainage ditches, streetlights and plumbing.

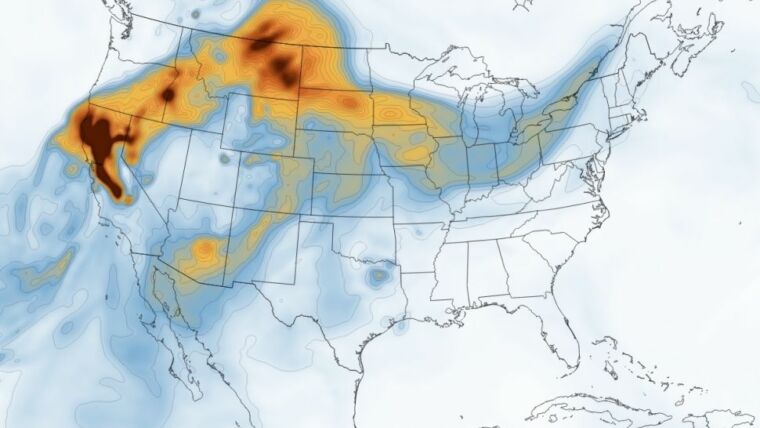

Here in the fertile floodplains of the Rio Grande Valley, the average temperature is creeping upward, according to the latest National Climate Assessment. In 2011, parts of Texas saw 100 days with temperatures above 100 F. Researchers connected the extreme heat wave, in part, to human-induced climate change. Projections suggest that heat waves stand to be longer and hotter. Nighttime low temperatures are creeping up, as well. Then there’s this grim irony: Even as drought could become more prevalent, extreme precipitation events, like the kind that inundate the colonias, are also more likely by midcentury.

More than 500,000 people live in the colonias of borderland Texas, with Hidalgo County having one of the highest concentrations of these unplanned neighborhoods, according to a 2015 report from the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Most of them are poor. More than 40 percent of colonia residents live below the poverty line, and 20 percent live at the line, according to the report. Homelessness is rare, because residents take care of their neighbors. Small homes can host multiple families. About a third of the people living in colonias don’t have running water; that’s one of the highest concentrations in the country, according to the Rural Community Assistance Partnership. In the colonias, that has led to higher rates of hepatitis A, salmonellosis, shigellosis and tuberculosis compared with the rest of the state, according to researchers at the University of Texas.

About a quarter of everyone who lives in colonias are in the United States illegally, according to the Federal Reserve report, and many of them are farmworkers.

The sum of acute challenges here makes climate change a kind of white noise, usually. It’s not as urgent as the threat of being deported (parents make plans with neighbors to meet the school bus in case they’re swept up in a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement raid). Yet farmworkers say that rising temperatures are making their lives harder. Now, not just in the future.

Farmworkers labor in the sun during dangerous heat waves because they can’t afford to take days off, said Jose Torres, a former farmworker who is now a paralegal at Texas RioGrande Legal Aid. Complaining about conditions, such as dirty or warm water, a lack of bathrooms or a 105 F day, could result in being blacklisted. Farm bosses want people who work, not who complain, Torres said.

Many farmworkers grew up in abject poverty. Many have never experienced fair treatment as an employee, by receiving medical care or pay for a sick day, he said.

“When I was growing up, my brother and I and my sister would ask my mother and father, ‘Why am I poor; why is it that I have to live under these conditions?’ And the answer was because that was the way God wants. As I grow older, I say, ‘What have I ever done to be punished?’ And so, an act of God? To hell with that shit.”

There are practical reasons why farmworkers are concerned about climate change, said Robert Bullard, a professor of urban planning and environmental policy at Texas Southern University. He helped found the environmental justice movement in the 1970s. It’s not something people look at as happening 50 years from now, he said.

“You’re talking about vulnerabilities being heightened and risk being heightened and awareness being heightened,” Bullard said. “It’s because people are closer to the issue, as opposed to some places where it’s more theoretical and not necessarily seeing the impacts up close and personal.”

Farmworkers rise at 3 or 4 a.m. to beat the heat. In July, at the height of the picking season, low temperatures are often in the 80s and rise quickly above 100 F. Workers wear pants and long-sleeved shirts to guard against pesticides that coat the crops.

“You have to tell them, drink water, drink water, make your little heart cool off, get a drink of water then go back to work,” Martinez said as he stood in an onion field where he would soon bring a crew of 150 to clip the crops. “I keep telling them on the radio, especially when it gets in the 90s.”

It’s not just the fields that become oppressive in the heat, said Sylvia Murphy, who leads educational sessions on the dangers of heat stress for Motivation, Education and Training Inc., which advocates for farmworkers.

She said packing sheds, which rarely have air conditioning, can become dangerous. Workers use the sheds, which often have metal roofs, to transfer vegetables and fruits from bins into boxes and mesh bags so they can be transported to roadside stands, farmers markets, grocery stores and Walmart.

“It’s a constant movement, so therefore your body, without you realizing it, you’re using energy. You’re using whatever little liquid is in your body, so you’re sweating it out. You’re dehydrating yourself, and you might be on the verge of heat stress or even … heatstroke,” she said.

Recurrent dehydration can have serious health consequences, and medical researchers said the incidents are on the rise in South Texas.

As global temperatures climb, so, too, does the incidence of fatal kidney disease. It’s on the rise among farmworkers throughout the world. A 2014 study of farmworkers in Central America, many of them young males, found that a high number died from an unknown kidney disease. Researchers connected the deaths to recurrent dehydration and a heavy workload in hot conditions. It has killed about 20,000 people in Central America in the last 20 years, according to researchers at Boston University.

Farmworkers don’t escape the heat when they leave the fields. Several families often crowd into single homes in colonias, said Daniela Dwyer, an attorney and director of the farmworker division at Texas RioGrande Legal Aid. If more than a dozen people are in a home, families and workers will rotate using the stove, making the house hot for prolonged periods, she said.

“It’s really important, especially for what few hours they are sleeping, that people be able to bring their body temperature down,” Dwyer said. “So while it’s expensive for them and many people don’t have AC, I wouldn’t consider AC a luxury for farmworkers. It’s a necessity to bring their temperatures down.”

On a recent day, Maria Romero walked through her colonias to hand out literature in Spanish about the dangers of the Zika virus. The flyer detailed the symptoms of the disease and how to prevent it by emptying buckets and draining ditches and other areas where mosquitoes lay eggs. Zika terrorized South America in recent years by leading to the births of babies with abnormally small heads. Now it’s moving north and is close to the Texas borderlands, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Growling dogs on chains guarded a number of homes approached by Romero.

Her house, like many in the colonias, is up on cinder blocks to mitigate damage from repeated flooding. But she still finds a place where the boards are rotted. There are no drainage ditches, and heavy rains can inundate the neighborhoods. Toilets overflow, and sewage spills into homes. Children are sometimes carried across the water to board school buses. Dead animals wash up on front lawns.

“When it rains a lot, it will be flooded for up to three to four days,” Romero said, speaking through a translator. “When it rains a lot more, it’s for a week. When children go outside and play, they’ll get a rash.”

Some see the changes as one cost of living in a harsh land.

People will adapt over time, even if temperatures are increasing, said Manuel Gabriel Ortega, 39, who grows cotton, grain sorghum and sugar cane. Farmers have to grow crops whether it’s hot or cold, wet or dry. And they are used to making changes when they need to, he said.

“I think as a farmer, as someone with crops, the seed companies, they’re always one step ahead of the game,” he said. “If you need a seed that’s a little more drought-tolerant, they’re going to have it.”

But those in the fields say farmers have an easier time weathering the changes because they have insurance. When heat causes blight that ruins a 50-acre field of onions, the farmer can be compensated, said Linda Martinez, who runs a crew of farmworkers. The workers don’t have that choice, she said, and it’s driving more young people away from the fields and into restaurants, Walmart and other places where the work is not so grueling.

That makes it harder to find workers, Martinez said. In the past, she could have a crew of 300. Now, it’s hard to get 150 because younger people are turning to other work.

“There used to be a lot more people who clipped onions than there is now, because all the young generations don’t want to work in the field anymore,” Martinez said.