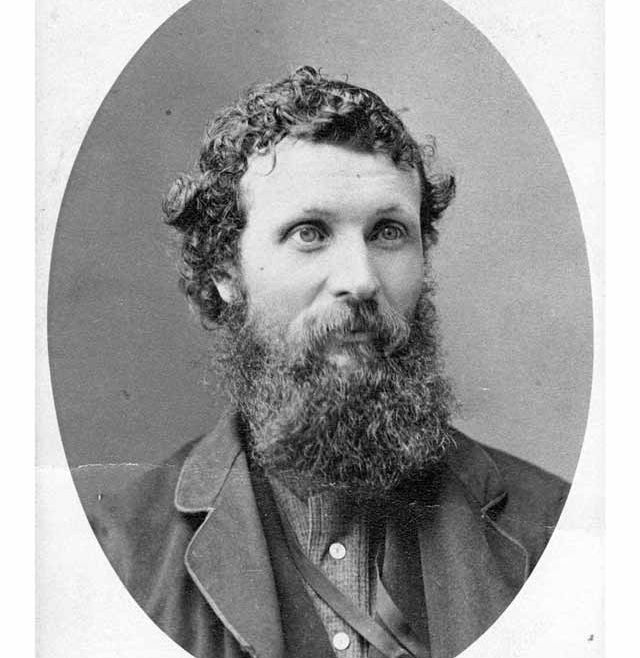

While I am by no means a John Muir scholar, my friend and former Sierra Club President (who signed my Life Member certificate in 1989 in that capacity) and fellow Sierra Club Foundation Board member Richard Cellarius does know a great deal about the founder of Sierra Club who also appears on the California Quarter. And it is fitting that on his birthday today we remember John Muir. What follows is what Richard sent out this morning.

Dear Friends,

On the occasion of 176th Anniversary of John Muir’s birth, I am pleased to send another in my series of messages celebrating Muir and his accomplishments and wisdom. I also note that 2014 is the 100th Anniversary of Muir’s death in Pasadena at age 76 on Christmas eve 1914.

I am taking different approach to my this year, since I am in Bangkok, Thailand at a meeting of the IUCN Commission on Environmental, Economic and Social Policy, and have not had my usual opportunity to research Muir’s stories and wisdom.

However, Fred Heutte, the Sierra Club’s volunteer Climate Chaos policy guru, recently sent out a review of a recent book about Muir’s travels in Alaska, ‘John Muir and the Ice That Started a Fire’ by Kim Heacox. The review, by James Sullivan in the Boston Globe, contains some wonderful quotes from Muir and gives a good flavor of Muir’s penchant for adventure, his natural philosophy, and his wisdom.

I have not had the opportunity to obtain and explore the book itself, but it certainly appears an important addition to the growing bibliography on Muir.

You will find earlier Muir Birthday messages on my website at http://muir.cellarius.org/.

Happy Birthday Johnnie.

Richard

Richard Cellarius

richard@cellarius.org

on behalf of

John Muir 1838 muir@cellarius.org

‘John Muir and the Ice That Started a Fire’ by Kim Heacox

By James Sullivan | Globe Correspondent April 01, 2014

On one of his many treks in Alaska, the naturalist John Muir chided a companion for staying back at camp while Muir enjoyed a spectacular day out among the glaciers.

“I’ve been wandering through a thousand rooms of God’s crystal temple,”

he reported. “Such purity, such color, such delicate beauty! I was tempted to stay there and feast my soul, and softly freeze, until I would become part of the glacier. What a great death that would be.”

Muir, the preservationist who helped convince Theodore Roosevelt that untrammeled land was priceless, gladly gave his life to the natural world. As Alaska nature writer Kim Heacox notes in his sure-handed biography “John Muir and the Ice That Started a Fire,” Muir was a bird lover and a botanist, but he reserved his greatest ardor for the “blue ice rivers” that helped shape the entire planet. A globally influential figure in his lifetime, the “self-styled poetico-geologist” was to glaciers, the biographer suggests, as “Jacques Cousteau would be to the oceans and Carl Sagan to the stars.”

For Muir, the son of a strict Presbyterian Scotsman, the wilderness was a vast cathedral. He studied Darwin’s theory of evolution, but not to the exclusion of a supreme being — “an Intelligence” — behind it.

“Every cell, every particle of matter in the world requires a Captain to steer it into its place,” he once jotted in the margin of a book.

Awe was Muir’s daily pursuit. With friends once on a hike in the High Sierras, he scoffed at their elaborate picnic as he nibbled on a piece of crust. “To dine with a glacier on a sunny day is a glorious thing and makes common feasts of meat and wine ridiculous,” he wrote to his sister. “A glacier eats hills and drinks sunbeams.”

Heacox, whose last book, “The Only Kayak,” was an elegant memoir of living in ever-changing Alaska, seems ideally matched to his subject.

Over time, the mighty glaciers have been forced to retreat. Muir, Heacox claims, may have been the first naturalist to attribute the phenomenon to global warming. Muir Glacier, named for the explorer after his first visits (beginning in 1879) to what is now Glacier Bay National Park in Alaska, terminates 35 miles farther north than it did in Muir’s time.

“Nothing dollarable is safe,” said Muir. With swift strokes, the author sets the wanderer’s work in the context of the stampeding progress of the late 19th century, when Carnegie forged steel, Edison illuminated the cities, and materialist expansion “put us on the road to universal abundance.”

Muir’s journeys have been chronicled in more exhaustive detail, most recently in the 2009 biography “A Passion for Nature,” by Donald Worster. But Heacox’s book deftly zeroes in on the environmentalist’s glacier studies to imply the urgency of climate change awareness and activism.

Muir’s pivotal camping trip in Yosemite with Roosevelt, which helped inspire the president to set aside 230 million acres of federal land (more than California and Texas combined), takes the book on a vivid detour, with “the president fit for a Kipling novel, dressed in his khaki jodhpurs and a Rough Rider hat” and Muir “in his loose-fitting suit, the hobo intellectual, a sprig of cedar poked through a buttonhole.”

In a graceful coda noting the passage of the 1964 Wilderness Act and other conservationist legislation, Heacox transfers Muir’s mind-set into the present day. “The last frontier is not Alaska, outer space, the oceans, or the wonders of technology,” he writes. “It’s open- mindedness.”

Muir, who found heaven on Earth, would have said so himself.

John Muir and the Ice That Started a Fire: How a Visionary and the Glaciers of Alaska Changed America

Author: Kim Heacox

Publisher: Lyons

Number of pages: 264

Book price: $25.95

http://www.bostonglobe.com/arts/books/2014/03/31/book-review-john-muir-and-ice-that-started-fire-kim-heacox/GvtJvlGPbNQ2aAWS2pJFMN/story.html